School

STUDENTS ARE OFTEN SURPRISED to find out how much I hated school when I was a kid. I have a big mix of complaints about my schooling, but the main one is that I always felt school was so boring.  It's an eternal complaint of a lot of students, and I was no different. It felt like long years (years!) of being forced to do things I didn't want to do.

It's an eternal complaint of a lot of students, and I was no different. It felt like long years (years!) of being forced to do things I didn't want to do.

IT DIDN'T START OUT THAT WAY of course. When I was born, I certainly didn't hate school yet. In fact, although I don't remember it much, the record seems to show that my time in kindergarten and first grade, and even later on in primary school (we called it "elementary school"), must have been okay. I have vague memories of things we did, and of some of my teachers. They aren't glowing memories, but I think kids at that age pretty much take things as they come without too many questions.

A BIG FACTOR in my case was that we moved around a lot as a family in that time of my life. I went to kindergarten and first grade in one place; we moved and I spent from grade 2 into grade 5 in another place; we moved again and I spent time through grade 6 in another school; I spent grade 7 in yet another school; and then finished (grades 8 through 12) in still a different school. Now, as an international school teacher, I find myself amazed again and again at the resilience and  strong personalities of my own students, many of whom move not only from city to city but country to country (and language to language) with what looks like such ease. It was hard enough for me to feel that I fit in whenever my family moved--and we stayed in the same country all that time. I always felt like the "new kid," even after other kids came in after me. I became less and less talented at making friends, rather than the reverse. One result is that I became a quiet little student. Many teachers mistakenly assumed, as a result, that I was a studious child. I was not.

strong personalities of my own students, many of whom move not only from city to city but country to country (and language to language) with what looks like such ease. It was hard enough for me to feel that I fit in whenever my family moved--and we stayed in the same country all that time. I always felt like the "new kid," even after other kids came in after me. I became less and less talented at making friends, rather than the reverse. One result is that I became a quiet little student. Many teachers mistakenly assumed, as a result, that I was a studious child. I was not.

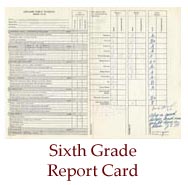

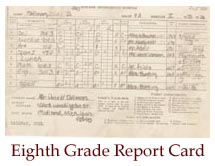

IN FACT, as the record shows in my report cards, I became less and less talented as a student, as well. I had my strengths--it's possible I read more books than any of the English teachers I ever had in school, and I liked art and social studies, and I could make myself interested in science if I cared enough--but even my strengths didn't always show in my report cards. Nor did it mean more interest in classes. The older I got, the more useless and boring everything seemed.  I started to wonder if perhaps all of life was like this, and things would just get more and more boring throughout whatever career I chose, until finally I turned into a middle-aged man whose skull was ready to collapse from the vacuum of boredom that had been created over time.

I started to wonder if perhaps all of life was like this, and things would just get more and more boring throughout whatever career I chose, until finally I turned into a middle-aged man whose skull was ready to collapse from the vacuum of boredom that had been created over time.

IN MY BETTER MOMENTS, though, I knew that things would improve the second I graduated from high school. I didn't want to just get out of high school, or maybe I would have just dropped out. I didn't have any great rock-and-roll dream to carry me without a diploma. No, I knew that I wanted to graduate from high school. I knew that I wanted to go to college, and I knew that college life would be a lot more interesting, a lot more independent, and frankly a lot more cool than high school was ever going to be. And knowing that I wanted to graduate was the key to my philosophy in middle school (which I barely remember as a blur) and high school (which I remember vividly as torture). That philosophy: Just lay low, and eventually it will be over. I didn't act out in class, or spray paint the walls of the school building. I wasn't rude to my teachers, and I didn't skip classes. Most importantly, I always listened in class to what was important--or at least, important in terms of any information I'd have to know later on a quiz or test.

THAT WAS THE KEY: LISTENING. Listening, for me, was a substitute for doing actual work or studying of any kind. I never took home a book to "study" when I was in high school, and I'm still not quite sure what that word means. (I am quite sure most of my students don't know, either.) When other kids said they were "studying," did that mean they were reading their textbooks over and over and over? Were they doing extra math problems, or memorizing lists? Or was "studying" just a code word for sitting in your bedroom and avoiding schoolwork altogether? I generally (but not always) did my homework, since that was one way to get out of high school. But I only did whatever homework I could do in school, either during class while the teacher was talking or during lunch. And I generally (but not always) wrote essays or made projects or whatever those assignments were, since that was also a way to get out of high school. They required work outside of school, but I was generally always a quick writer of essays, and we never really had that many projects to do.

IT STILL AMAZES ME how many students don't listen to information the first time it's given in class. That's the quickest, easiest shortcut to enjoying your time outside of school. For some reason, lots of students would rather waste their time inside of school, and then spend time outside of school making up for it. A lousy system if there ever was one. If you just listen the first time, it all makes a lot more sense, and it's all easier to remember. (Maybe it's even easier to learn, although I can't say I learned much of what was taught to me in high school. Who can say that? It's all part of the game, and all part of why I wanted out so badly.) I can tell you from experience, the system worked for me. I made it through high school, with time to devote to things I really thought were important.

BUT HEY, DIDN'T YOU HATE IT? Well, yes. Nearly every minute of every hour of every school day. There were a few bright spots, mainly when I had teachers I liked. (My favorite teacher in high school was my Spanish teacher, Mr. Norm Neher.) But it's also true that I thought most of what I was being taught was useless, and I didn't see why it had to be so boring. A lot of my disappointment with school, though, was my own fault. I was a loner, never had many friends, and didn't really take advantage of what most of my own students know is the best part of school: the social part. But you can do that and listen, too.

MORE THAN THAT, I now realize how much potential school really has. It's the answer I have to the common student question, "Why do we have to know this?" (I always felt that way about anything in math class, personally. My students often feel that way about classic literature.) My answer is, You never really need to know anything. Sure, learning to read and learning arithmetic, which most of us do when we're in primary school, are pretty essential in life. But chemical equations? Trigonometry? Shakespeare? Most of what you learn in high school will not only be personally useless to you, it is in reality useless to most people in the world. Hollywood movies are useless, every note of music you've ever heard is useless.

MORE THAN THAT, I now realize how much potential school really has. It's the answer I have to the common student question, "Why do we have to know this?" (I always felt that way about anything in math class, personally. My students often feel that way about classic literature.) My answer is, You never really need to know anything. Sure, learning to read and learning arithmetic, which most of us do when we're in primary school, are pretty essential in life. But chemical equations? Trigonometry? Shakespeare? Most of what you learn in high school will not only be personally useless to you, it is in reality useless to most people in the world. Hollywood movies are useless, every note of music you've ever heard is useless.  But it's not a matter of usefulness. It's a matter of the kind of person you want to be. In the end, it is better to know, than not to know. A person who knows about the stars, and about plants, who speaks several languages, who has read the classics, that person is just better off in this world than a person who is ignorant of those things. A knowledgeable and articulate taxi driver is a better taxi driver; a knowledgeable and articulate doctor is a better doctor. To say that a doctor does not "need" Shakespeare, and a taxi driver does not "need" astronomy, is to entirely miss the point of your education. (Besides which, it underestimates both taxi drivers and doctors.) If you one day win the lottery and are able to live an existence without ever worrying about money, I hope one of the things you'd do with your leisure (between the parties) is try to know more, try to learn more, try to create more. All things school is designed for, even if it is often buried under hours of boredom. I didn't quite get that until later in life.

But it's not a matter of usefulness. It's a matter of the kind of person you want to be. In the end, it is better to know, than not to know. A person who knows about the stars, and about plants, who speaks several languages, who has read the classics, that person is just better off in this world than a person who is ignorant of those things. A knowledgeable and articulate taxi driver is a better taxi driver; a knowledgeable and articulate doctor is a better doctor. To say that a doctor does not "need" Shakespeare, and a taxi driver does not "need" astronomy, is to entirely miss the point of your education. (Besides which, it underestimates both taxi drivers and doctors.) If you one day win the lottery and are able to live an existence without ever worrying about money, I hope one of the things you'd do with your leisure (between the parties) is try to know more, try to learn more, try to create more. All things school is designed for, even if it is often buried under hours of boredom. I didn't quite get that until later in life.

THEN WHY DID YOU BECOME A TEACHER? One thing I knew I'd never be for a career, and that's a teacher. My parents had both been teachers. As a student, I'd seen enough teachers in action. Or, inaction. Who wanted any part of that? But things happened to me after I graduated from high school, and finally went--as a journalism major--to Michigan State University. Just as I had imagined, things were indeed more interesting, more independent, and more cool. More to the point here, I eventually had an influential professor named Vince Lombardi. (There's a famous Vince Lombardi, but this is a different one.) Long story short, I did a big turnaround on becoming a teacher.

THEN WHY DID YOU BECOME A TEACHER? One thing I knew I'd never be for a career, and that's a teacher. My parents had both been teachers. As a student, I'd seen enough teachers in action. Or, inaction. Who wanted any part of that? But things happened to me after I graduated from high school, and finally went--as a journalism major--to Michigan State University. Just as I had imagined, things were indeed more interesting, more independent, and more cool. More to the point here, I eventually had an influential professor named Vince Lombardi. (There's a famous Vince Lombardi, but this is a different one.) Long story short, I did a big turnaround on becoming a teacher.

THERE ARE LOTS OF GOOD REASONS TO BECOME A TEACHER. You get to continue the wonderful practice of having summer vacations, even into adulthood. You get some control over your own working life, in your own classroom. As I've discovered now in the second half of my teaching career, you can also travel and see the world teaching in international schools, living in excellent locations, which is not at all a bad racket. Unlike what it says on a lot of mugs and refrigerator magnets, you don't necessarily "touch the future" or change the world. But you do get to know a lot of great people every year, in the form of new and interesting students. Occasionally you're--without exaggeration--the best thing in somebody's life, just when they need it. And in the back of your mind, if you're me, you can have the idea that you're making things at least a little better for some other kids than it was for you.

Unlike what it says on a lot of mugs and refrigerator magnets, you don't necessarily "touch the future" or change the world. But you do get to know a lot of great people every year, in the form of new and interesting students. Occasionally you're--without exaggeration--the best thing in somebody's life, just when they need it. And in the back of your mind, if you're me, you can have the idea that you're making things at least a little better for some other kids than it was for you.

DON'T WORRY, I'm not suggesting you become a school teacher. But I am suggesting that, whatever you become, you also become a teacher. Everyone should be a teacher. Every accountant should be a teacher. Every engineer should be a teacher. It should go without saying that every parent should be a teacher. It's a way the world can be a better, more loving, and civilized place--not the huge, entire globe, but for you and the people around you. You teach them. How do you teach the people around you? Easy: By example. By being a better, more loving, and more civilized person.

THAT'S WHAT EDUCATION, as opposed to schooling, can be at its best. Trying hard every day to be more humane and more decent to others. To all others, not just the ones who don't aggravate us, or only the ones who treat us well first. Respecting everyone, being good to everyone, that's teaching by example. That's what should be happening in board rooms, living rooms, operating rooms, and yes classrooms, every day. It's not measured by report cards, or tests, or grades, and it's not limited to any school building. It's measured inside, and like it or not, you get to grade yourself. And like it or not, it means school continues, forever, every single day of your life. If you're lucky, the lessons you teach will continue even beyond your own life.

I'LL SEE YOU in school.

--Mr. Tallman

Return to TallMania

It's an eternal complaint of a lot of students, and I was no different. It felt like long years (years!) of being forced to do things I didn't want to do.

It's an eternal complaint of a lot of students, and I was no different. It felt like long years (years!) of being forced to do things I didn't want to do. strong personalities of my own students, many of whom move not only from city to city but country to country (and language to language) with what looks like such ease. It was hard enough for me to feel that I fit in whenever my family moved--and we stayed in the same country all that time. I always felt like the "new kid," even after other kids came in after me. I became less and less talented at making friends, rather than the reverse. One result is that I became a quiet little student. Many teachers mistakenly assumed, as a result, that I was a studious child. I was not.

strong personalities of my own students, many of whom move not only from city to city but country to country (and language to language) with what looks like such ease. It was hard enough for me to feel that I fit in whenever my family moved--and we stayed in the same country all that time. I always felt like the "new kid," even after other kids came in after me. I became less and less talented at making friends, rather than the reverse. One result is that I became a quiet little student. Many teachers mistakenly assumed, as a result, that I was a studious child. I was not. I started to wonder if perhaps all of life was like this, and things would just get more and more boring throughout whatever career I chose, until finally I turned into a middle-aged man whose skull was ready to collapse from the vacuum of boredom that had been created over time.

I started to wonder if perhaps all of life was like this, and things would just get more and more boring throughout whatever career I chose, until finally I turned into a middle-aged man whose skull was ready to collapse from the vacuum of boredom that had been created over time.

MORE THAN THAT, I now realize how much potential school really has. It's the answer I have to the common student question, "Why do we have to know this?" (I always felt that way about anything in math class, personally. My students often feel that way about classic literature.) My answer is, You never really need to know anything. Sure, learning to read and learning arithmetic, which most of us do when we're in primary school, are pretty essential in life. But chemical equations? Trigonometry? Shakespeare? Most of what you learn in high school will not only be personally useless to you, it is in reality useless to most people in the world. Hollywood movies are useless, every note of music you've ever heard is useless.

MORE THAN THAT, I now realize how much potential school really has. It's the answer I have to the common student question, "Why do we have to know this?" (I always felt that way about anything in math class, personally. My students often feel that way about classic literature.) My answer is, You never really need to know anything. Sure, learning to read and learning arithmetic, which most of us do when we're in primary school, are pretty essential in life. But chemical equations? Trigonometry? Shakespeare? Most of what you learn in high school will not only be personally useless to you, it is in reality useless to most people in the world. Hollywood movies are useless, every note of music you've ever heard is useless.  But it's not a matter of usefulness. It's a matter of the kind of person you want to be. In the end, it is better to know, than not to know. A person who knows about the stars, and about plants, who speaks several languages, who has read the classics, that person is just better off in this world than a person who is ignorant of those things. A knowledgeable and articulate taxi driver is a better taxi driver; a knowledgeable and articulate doctor is a better doctor. To say that a doctor does not "need" Shakespeare, and a taxi driver does not "need" astronomy, is to entirely miss the point of your education. (Besides which, it underestimates both taxi drivers and doctors.) If you one day win the lottery and are able to live an existence without ever worrying about money, I hope one of the things you'd do with your leisure (between the parties) is try to know more, try to learn more, try to create more. All things school is designed for, even if it is often buried under hours of boredom. I didn't quite get that until later in life.

But it's not a matter of usefulness. It's a matter of the kind of person you want to be. In the end, it is better to know, than not to know. A person who knows about the stars, and about plants, who speaks several languages, who has read the classics, that person is just better off in this world than a person who is ignorant of those things. A knowledgeable and articulate taxi driver is a better taxi driver; a knowledgeable and articulate doctor is a better doctor. To say that a doctor does not "need" Shakespeare, and a taxi driver does not "need" astronomy, is to entirely miss the point of your education. (Besides which, it underestimates both taxi drivers and doctors.) If you one day win the lottery and are able to live an existence without ever worrying about money, I hope one of the things you'd do with your leisure (between the parties) is try to know more, try to learn more, try to create more. All things school is designed for, even if it is often buried under hours of boredom. I didn't quite get that until later in life. THEN WHY DID YOU BECOME A TEACHER? One thing I knew I'd never be for a career, and that's a teacher. My parents had both been teachers. As a student, I'd seen enough teachers in action. Or, inaction. Who wanted any part of that? But things happened to me after I graduated from high school, and finally went--as a journalism major--to Michigan State University. Just as I had imagined, things were indeed more interesting, more independent, and more cool. More to the point here, I eventually had an influential professor named Vince Lombardi. (There's a famous Vince Lombardi, but this is a different one.) Long story short, I did a big turnaround on becoming a teacher.

THEN WHY DID YOU BECOME A TEACHER? One thing I knew I'd never be for a career, and that's a teacher. My parents had both been teachers. As a student, I'd seen enough teachers in action. Or, inaction. Who wanted any part of that? But things happened to me after I graduated from high school, and finally went--as a journalism major--to Michigan State University. Just as I had imagined, things were indeed more interesting, more independent, and more cool. More to the point here, I eventually had an influential professor named Vince Lombardi. (There's a famous Vince Lombardi, but this is a different one.) Long story short, I did a big turnaround on becoming a teacher. Unlike what it says on a lot of mugs and refrigerator magnets, you don't necessarily "touch the future" or change the world. But you do get to know a lot of great people every year, in the form of new and interesting students. Occasionally you're--without exaggeration--the best thing in somebody's life, just when they need it. And in the back of your mind, if you're me, you can have the idea that you're making things at least a little better for some other kids than it was for you.

Unlike what it says on a lot of mugs and refrigerator magnets, you don't necessarily "touch the future" or change the world. But you do get to know a lot of great people every year, in the form of new and interesting students. Occasionally you're--without exaggeration--the best thing in somebody's life, just when they need it. And in the back of your mind, if you're me, you can have the idea that you're making things at least a little better for some other kids than it was for you.